Vienna Vampire Stories

Vienna is known as a city of music, art and indulgence. Less well known is the fact that the city also played a key role in the history of vampirism – not as a place of horror, but as a centre of the Enlightenment. When reports of alleged undead figures began to unsettle the Habsburg Monarchy, it was a Viennese physician who set out for the eastern regions of the empire to bring an end to this myth: Gerard van Swieten.

Gerard van Swieten – Physician and Enlightener

Gerard van Swieten was born on 7 May 1700 in the Netherlands. He was part of a new generation of physicians who relied not on myths, but on scientific knowledge. As a student of the renowned physician Hermann Boerhaave, he quickly gained international recognition – including within the Austrian Empire.

In 1745, Maria Theresa brought van Swieten to Vienna and appointed him her personal physician. The ruling Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary and Bohemia was never crowned empress, yet she went down in history as the most powerful woman of the Habsburg dynasty. Van Swieten soon became one of her most important advisors, not only when it came to medical matters but also regarding reforming topics such as education and public health. A deep scepticism towards superstition and an unwavering trust in science shaped his thinking – hallmarks of the Enlightenment.

Medicine was his great passion. Van Swieten fundamentally reformed medical education, introduced bedside teaching, established surgery as an independent discipline and brought leading scholars to Vienna. With new hospitals, laboratories, educational institutions and modern treatment methods, he laid the foundations for the so-called First Vienna School of Medicine. The initiative to create a botanical garden as aHortus Medicus also goes back to him – a visible legacy that remains to this day.

Vampire Fever in the Habsburg Empire

In the early 18th century, a genuine vampire fever swept across large parts of the Habsburg Empire. The epicentre was not Transylvania, but what is now Serbia and the southeastern border regions of the empire, where reports multiplied of dead people allegedly returning from their graves. Fear drove communities to exhume bodies and search for “suspicious” signs: supposedly grown hair and nails or blood around the mouth were considered clear evidence of vampirism. Panic ran so deep that impalement and cremation became common measures.

On 21 July 1725, the term “Vampyri” appeared for the first time in the Wiener Zeitung (then known as the Wienerisches Diarium), used to describe alleged undead creatures said to haunt the living at night. With this, the vampire belief had reached the imperial court. Maria Theresa reacted to the unrest and ordered her personal physician to investigate the cases scientifically. Van Swieten soon concluded that the phenomena could be explained by epidemic illnesses accompanied by fever, which could cause hallucinations. In 1755, an imperial decree made the desecration of graves under the pretext of vampire defence a punishable offence; reports of vampirism and so-called magia posthuma were placed under censorship. From Vienna, the vampire fever was finally contained.

Van Swieten and Count Dracula

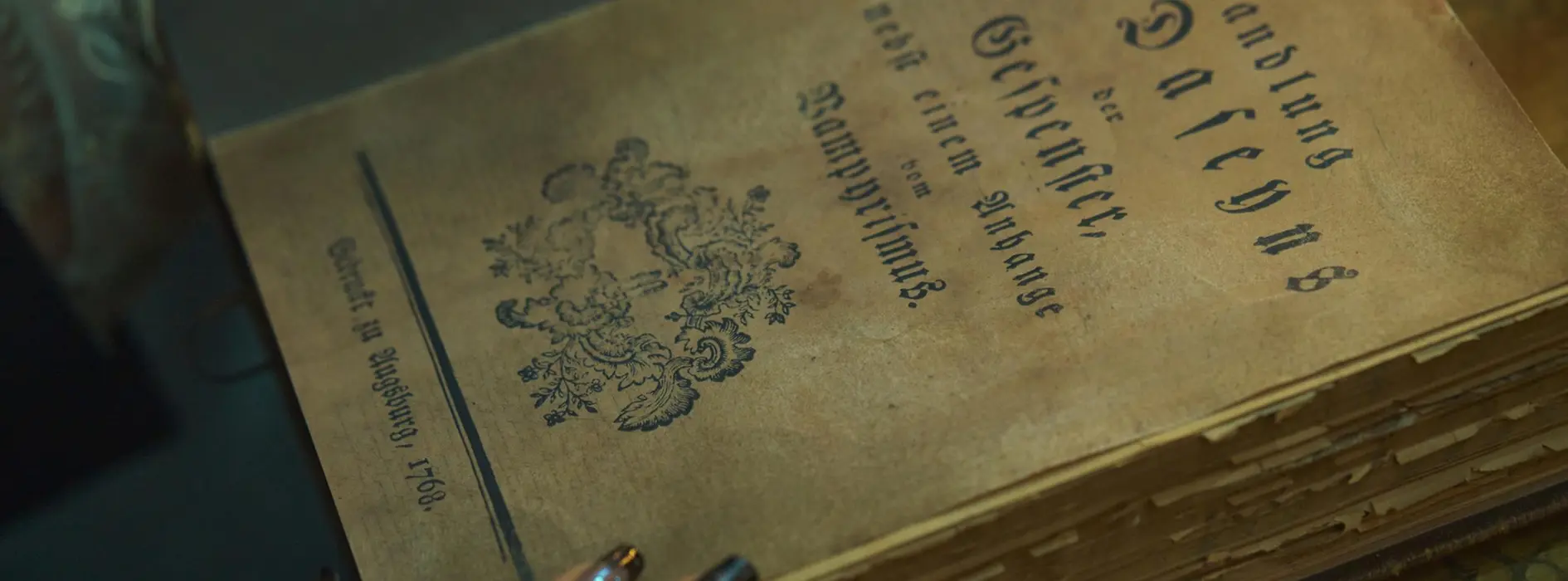

To put an intellectual end to the scare, van Swieten published his treatise “Abhandlung des Daseyns der Gespenster, nebst einem Anhange vom Vampyrismus” (“Treatise on the Existence of Ghosts, with an Appendix on Vampirism”) in 1768. He fundamentally examined the belief in vampires, ghosts and apparitions, describing it as a self-chosen darkness of the mind and a product of credulity and ignorance among the population. His work is preserved to this day at the Austrian National Library and is available online.

It is hardly surprising that a figure as remarkable as Gerard van Swieten later found his way into literature. He is widely regarded as the historical inspiration for vampire hunter Abraham van Helsing in Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula.

Van Swieten Today in Vienna

Gerard van Swieten is still present in Vienna’s cityscape today. One example is the Van Swieten Street in the 9th district. The Medical University of Vienna has also honoured him by naming its ceremonial hall the Van Swieten Hall.

Almost life-size, van Swieten can be found at the Maria Theresa Memorial between the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna and Naturhistorisches Museum Vienna, where he stands as one of the central “pillars of the throne” supporting the ruler. Inside the Naturhistorisches Museum, he also appears on the famous imperial painting on the main staircase – a work that has revealed surprising overpaintings and hidden figures during restorations in recent decades.

As director of the Court Library, the predecessor of today’s Austrian National Library, van Swieten modernised the collection and ensured the targeted acquisition of up-to-date scientific literature from Western Europe. A bust in the State Hall now commemorates him; it originates from his tomb monument in the Augustinian Church. Gerard van Swieten died on 18 June 1772 at Schönbrunn Palace.